The French writer’s debut novel was Les armoires vides of 1974; her most ambitious project Les années (The Years) has been called the “first collective autobiography”

The French writer’s debut novel was Les armoires vides of 1974; her most ambitious project Les années (TheYears) has been called the “first collective autobiography”

The story so far: The octogenarian French writer Annie Ernaux, often described as the “truth-teller” of France, has been awarded the Nobel Prize in literature for 2022. The Swedish Academy said while announcing the Prize on Thursday, October 6, that Ernaux was honoured “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory”.

Annie Ernaux: the early years

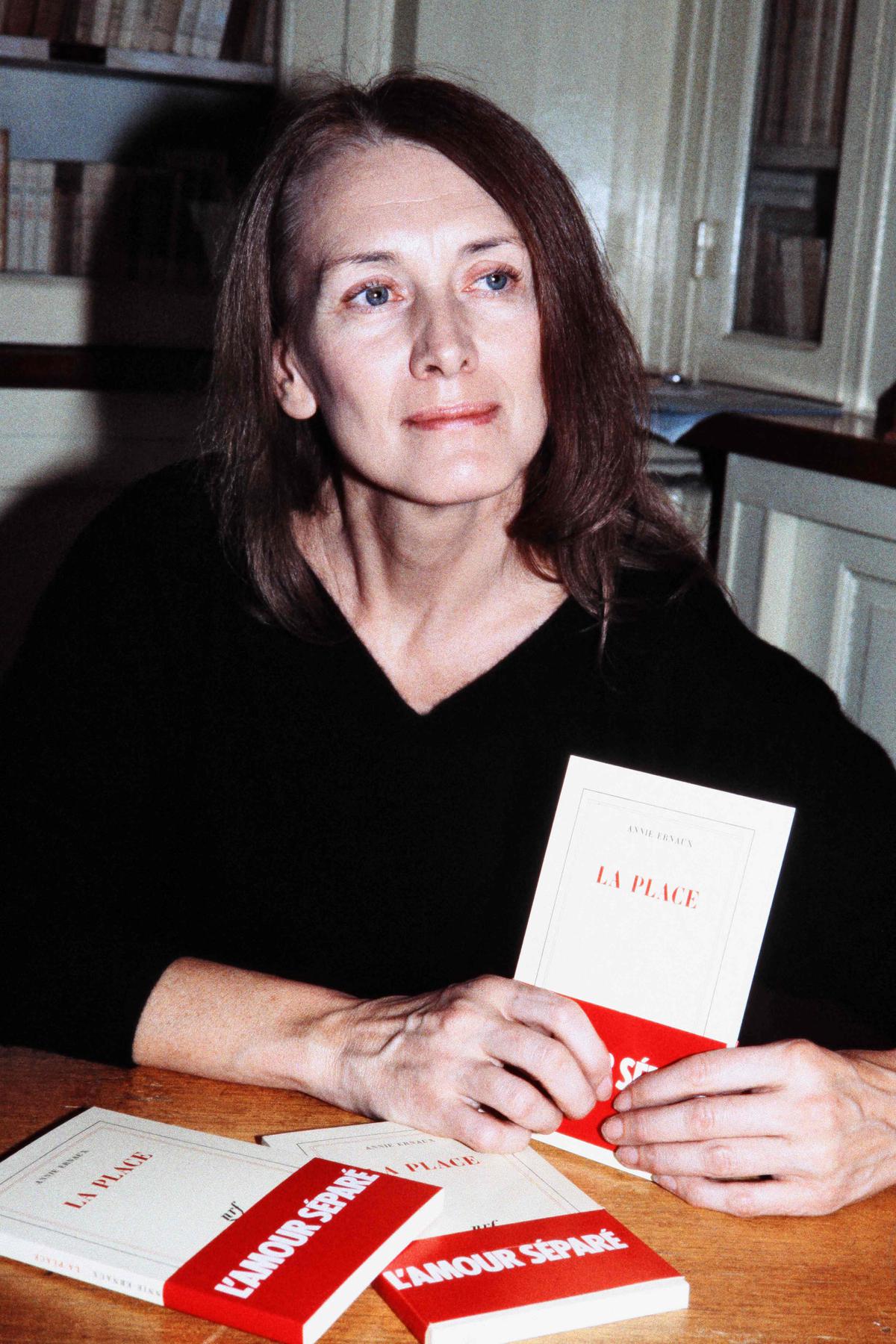

This file photo taken in Paris on November 12, 1984 shows French writer Annie Ernaux.

| Photo Credit: AFP

Born in September 1940, Ernaux grew up in the small town of Yvetot in Normandy, France. A lot of her work is rooted in this childhood setting where her parents ran a combined grocery store and café.

“Her setting was poor but ambitious, with parents who had pulled themselves up from proletarian survival to a bourgeois life, where the memories of beaten earth floors never disappeared but where politics was seldom broached,” the Swedish Academy points out in its biobibliography note on Ernaux.

In her debut novel, Les armoires vides (1974), translated and published in English as Cleaned Out in 1990, she began her investigation of her norman background, the Academy notes. Ernaux’s breakthrough work, however, was her fourth novel La place (1983), published in English as A Man’s Place in 1992. The Academy describes the 100-page novel as a “dispassionate portrait of her father and the entire social milieu that had fundamentally formed him”, where she uses her signature restrained and ethically motivated aesthetics. Ernaux was nominated for the International Booker prize in 2019 for her most ambitious project The Years (2017, Les années, 2008).

The writer, who left for university at the age of 18, calls herself a “class defector”, describing writing as a political act and the best thing she can do as the said defector. According to Agence France Presse, the writer has often been candid about the guilt and shame of climbing the social ladder, which she felt was an act of betrayal against her parents and their way of life.

She married in her mid-twenties and has two sons from the marriage, which ended in divorce in 1984, after which she raised her children alone. For years, she taught writing in Paris, where she still lives.

The works of the Nobel Laureate

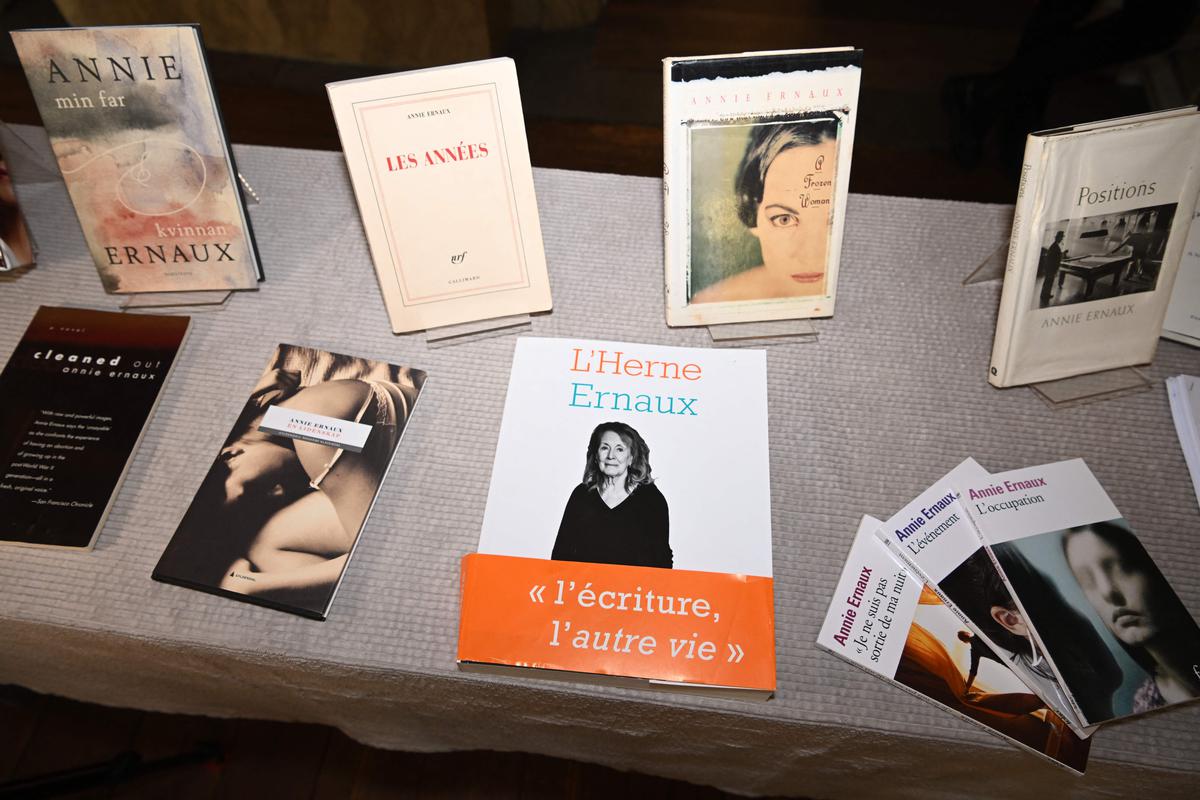

Books by French author Annie Ernaux are on display at the Swedish Academy after the announcement that Ernaux is this years winner of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature.

| Photo Credit: AFP

In her writing, Ernaux, almost as a pattern, examines a life marked by strong disparities regarding gender, language and class, using tools such as history and her own memory, which she regularly questions and describes as incomplete.

Madeleine Schwartz in The New Yorker describes Ernaux as an “unusual memoirist” who “distrusts her memory”, and does not hesitate in telling the reader where her memory goes blank, not revealing her past as an authoritative entity but “unpacking” it.

Her portrait of her father: A Man’s Place, and that of her mother: A Woman’s Story, are considered contemporary classics in France. She scrutinises her father, a practical man who did not let out much affection toward his family, almost in a cold fashion, through her exacting memory, revealing his unnatural adherence to societal standards and a shame he felt throughout his life. The Academy notes that contrastingly, in her mother’s portrait, Ernaux pays a wonderful tribute, albeit with similar brevity, to a strong woman, “who more than the father had been able to maintain her dignity, often in fraught conditions”.

In Simple Passion (1991), translated by Tanya Leslie, Ernaux writes: “From September last year, I did nothing else but wait for a man.” She blurs the line between fact and fiction to write about a two-year relationship with a foreigner, who was married. During the period, she is indifferent to everything else but actions related to this man, called A. in the novel. She would read newspaper articles about his country, write letters to him, choose clothes and make-up, change the sheets, arrange flowers, jot down things that might interest him, buy whiskey, imagine their time together, and thus fill “in time between two meetings.” The liaison, she writes, made her feel pain, sympathy and compassion for other people.

Ernaux pursues her passion as if she were seeking the meaning of existence and life. In narrating her connection with another individual, she also delves into the power of imagination and memory; and also arrives at the ultimate truth — “From the very beginning and throughout the whole of our affair, I had the privilege of knowing what we all find out in the end: the man we love is a complete stranger.” When the affair ends, and she is torn by sadness, Ernaux has an overriding urge one day to visit a building where she had had an abortion two decades back, “as if hoping that this past trauma would cancel my present grief.” With the Nobel Prize, the world outside France and Europe will discover the “truth-teller” of France who has chronicled life without borders in all her works. Exteriors, for instance, is a journal on contemporary life on the outskirts of Paris, filled with joy, loss, triumph, tragedy and chaos.

In The Years (2017), which won her “international recognition, a raft of followers, and literary disciples”, the French memoirist writes about her life from 1941 to 2006, because “all the images will disappear” – the images, “real or imaginary, that follow us all the way to sleep.”

In The Years, Ernaux narrates over 6 decades of time “through the lens of memory, impressions past and present, photos, books, songs, radio, television, advertising, and news headlines,” the Booker Prize Foundation notes. “Local dialect, words of the times, slogans, brands and names for ever-proliferating objects are given voice.” The use of these historical points of reference, and the frequent use of collective narration through “we”, makes The Years a one of its kind “collective autobiography”. Ernaux also looks at her life as an outsider, often describing her own past in the third person. German poet Durs Grünbein has lauded it as a pathbreaking “sociological epic” of the contemporary Western world.

A masterpiece from her production is the clinically restrained narrative about a 23-year-old narrator’s illegal abortion, L’événement (2000; Happening, 2001), the Academy mentions.

Ernaux’s thoughts on writing

Ernaux has said that writing is a political act, opening our eyes to social inequality. For this purpose she uses language as “a knife”, as she calls it, to tear apart the veils of imagination.

She has called herself an “archivist” and an “ethnologist of herself” rather than a writer of fiction, as she investigates her own memory and documents, how she felt about the events of her life as they were happening in the past, adding to it the gift of hindsight.

As the “truth-teller”, agony accompanies Ernaux in the reconstruction of her past as she “seeks to exceed the limit of the tolerable,” the Acadamey notes. In her book La honte (1996; Shame, 1998), she wrote: “I have always wanted to write the sort of book that I find it impossible to talk about afterward, the sort of book that makes it impossible for me to withstand the gaze of others.”

The memoirist told The New York Times two years ago about her dearest possession. “Frankly, I’d rather die now than lose everything I’ve seen and heard. Memory, to me, is inexhaustible.”